Location

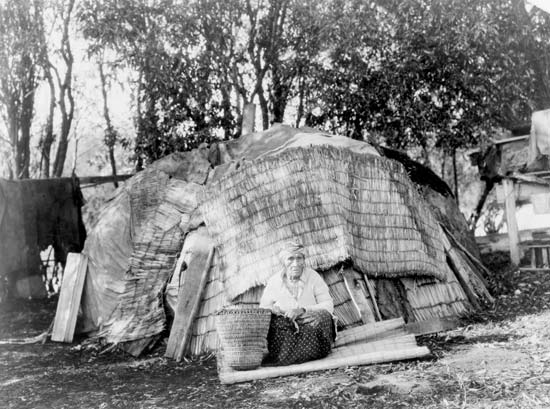

Shelter

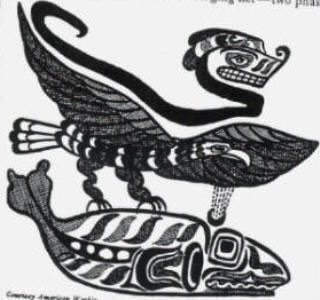

Food

Clothing

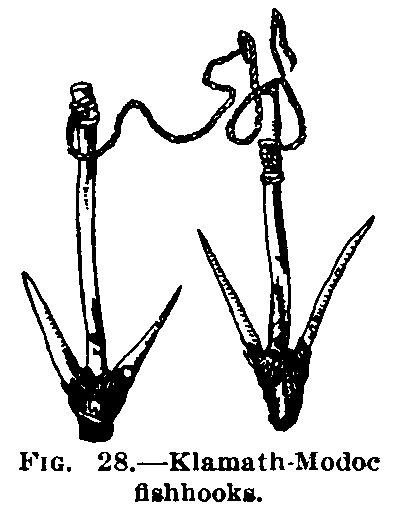

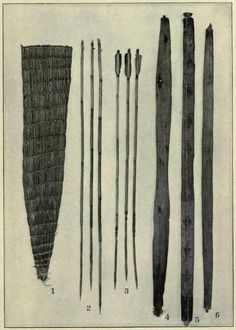

Tools and Weapons

Climate and Environment

In the old times Klamath' believed everything needed to live was provided for by Creator in this rich land east of the Cascades. The Klamath people still believe this. They saw success as a reward for virtuous striving and likewise as an assignment of spiritual favor, thus, "Work hard so that people will respect you", was the counsel of the elders. For thousands upon countless thousands of years the Klamath people survived by their industriousness. When the months of long winter nights were upon them, they survived on prudent reserves from the abundant seasons. Toward the end of March, when supplies dwindled, large fish runs surged up the Williamson, Sprague, and Lost River. At the place on the Sprague River where gmok'am'c first instituted the tradition, the Klamath's still celebrate the Return of c'waam Ceremony.

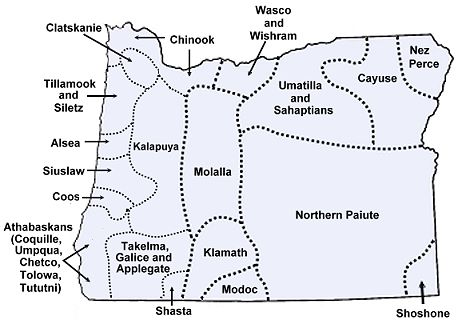

The six tribes of the Klamaths were bound together by ties of loyalty and Family, they lived along the Klamath Marsh, on the banks of Agency Lake, near the mouth of the Lower Williamson River, on Pelican Bay, beside the Link River, and in the uplands of the Sprague River Valley. The Modoc's lands included the Lower Lost River, around Clear Lake, and the territory that extended south as far as the mountains beyond Goose Lake. The Yahooskin Bands occupied the area east of the Yamsay Mountain, south of Lakeview, and north of Fort Rock. Everything needed was contained within these lands.

In 1826 Peter Skeen Ogden, a fur trapper from the Hudson's Bay Company, was the first white man to leave his footprints on Klamath lands. One hundred and seventy five years later those footprints have multiplied into the thousands, each leaving their marks on the lands and the Klamath Tribes. The newcomers came first as explorers, then as missionaries, settlers and ranchers. After decades of hostilities with the invaders, the Klamath Tribes ceded more than 23 million acres of land in 1864 and we entered the reservation era. They did, however, retain rights to hunt, fish and gather in safety on the lands reserved for the people "in perpetuity" forever.

From the first, Klamath Tribal members demonstrated an eagerness to turn new economic opportunities to their advantage. Under the reservation program, cattle ranching was promoted. In the pre-reservation days horses were considered an important form of wealth and the ownership of cattle was easily accepted. Tribal members took up ranching, and were successful at it. Today the cattle industry still remains an important economic asset for many. The quest for economic self-sufficiency was pursued energetically and with determination by Tribal members. Many, both men and women, took advantage of the vocational training offered at the Agency and soon held a wide variety of skilled jobs at the Agency, at the Fort Klamath military post, and in the town of Linkville. Due to the widespread trade networks established by the Tribes long before the settlers arrived, another economic enterprise that turned out to be extremely successful during the reservation period was freighting, in August 1889, there were 20 Tribal teams working year-round to supply the private and commercial needs of the rapidly growing county. A Klamath Tribal Agency - sponsored sawmill was completed in 1870 for the purpose of constructing the Agency. After signing the 1864 treaty, members of the Klamath Tribes were forcibly placed upon the Klamath Indian Reservation. At the time there was tension between the Klamath and the Modoc. A band of Modoc left the reservation to return to Northern California. They were defeated by the US Army after the Modoc War (1872–73), and were forced to return to Oregon.

By 1873, Tribal members were selling lumber to Fort Klamath and many other private parties, and by 1896 the sale to parties outside of the reservation was estimated at a quarter of a million board feet. With the arrival of the railroad in 1911, reservation timber became extremely valuable. The economy of Klamath County was sustained by it for decades. By the 1950s the Klamath Tribes were one of the wealthiest Tribes in the United States. They owned and judiciously managed for long term yield, the largest remaining stand of Ponderosa pine in the west. We were entirely self-sufficient. They were the only tribes in the United States that paid for all the federal, state and private services used by their members.

The Klamath tribe in Oregon was terminated under the Klamath Termination Act, or Public Law 587, enacted on August 13, 1954, as part of the US Indian termination policy. Under this act, all federal supervision over Klamath lands, as well as federal aid provided to the Klamath because of their special status as Indians, was terminated. The legislation required each tribal member to choose between remaining a member of the tribe, or withdrawing and receiving a monetary payment for the value of the individual share of tribal land. Those who stayed became members of a tribal management plan. This plan became a trust relationship between tribal members and the United States National Bank in Portland, Oregon. Of the 2,133 members of the Klamath tribe at the time of termination, 1,660 decided to withdraw from the tribe and accept individual payments for land.

After being terminated, the tribe was cut off from services for education, health care, housing and related resources. Termination directly caused decay within the tribe including poverty, alcoholism, high suicide rates, low educational achievement, disintegration of the family, poor housing, high dropout rates from school, disproportionate numbers in penal institutions, increased infant mortality, decreased life expectancy, and loss of identity.

The present-day Klamath Indian Reservation consists of twelve small non-contiguous parcels of land in Klamath County. These fragments are generally located in and near the communities of Chiloquin and Klamath Falls. Their total land area is 1.248 km² (308.43 acres). As is the case with many Native American tribes, today few of the Klamath tribal members live on the reservation; the 2000 census reported only nine persons resided on its territory, five of whom were white people. There is currently a dispute of blood quantum being discussed by tribal members.

There are currently around 4,500 enrolled members in the Klamath Tribes, with the population centered in Klamath County, Oregon. Most tribal land was liquidated when Congress ended federal recognition in 1954 under its forced Indian termination policy. Some lands were restored when recognition was restored. The tribal administration currently offers services throughout the county. (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Klamath_Tribes)

The six tribes of the Klamaths were bound together by ties of loyalty and Family, they lived along the Klamath Marsh, on the banks of Agency Lake, near the mouth of the Lower Williamson River, on Pelican Bay, beside the Link River, and in the uplands of the Sprague River Valley. The Modoc's lands included the Lower Lost River, around Clear Lake, and the territory that extended south as far as the mountains beyond Goose Lake. The Yahooskin Bands occupied the area east of the Yamsay Mountain, south of Lakeview, and north of Fort Rock. Everything needed was contained within these lands.

In 1826 Peter Skeen Ogden, a fur trapper from the Hudson's Bay Company, was the first white man to leave his footprints on Klamath lands. One hundred and seventy five years later those footprints have multiplied into the thousands, each leaving their marks on the lands and the Klamath Tribes. The newcomers came first as explorers, then as missionaries, settlers and ranchers. After decades of hostilities with the invaders, the Klamath Tribes ceded more than 23 million acres of land in 1864 and we entered the reservation era. They did, however, retain rights to hunt, fish and gather in safety on the lands reserved for the people "in perpetuity" forever.

From the first, Klamath Tribal members demonstrated an eagerness to turn new economic opportunities to their advantage. Under the reservation program, cattle ranching was promoted. In the pre-reservation days horses were considered an important form of wealth and the ownership of cattle was easily accepted. Tribal members took up ranching, and were successful at it. Today the cattle industry still remains an important economic asset for many. The quest for economic self-sufficiency was pursued energetically and with determination by Tribal members. Many, both men and women, took advantage of the vocational training offered at the Agency and soon held a wide variety of skilled jobs at the Agency, at the Fort Klamath military post, and in the town of Linkville. Due to the widespread trade networks established by the Tribes long before the settlers arrived, another economic enterprise that turned out to be extremely successful during the reservation period was freighting, in August 1889, there were 20 Tribal teams working year-round to supply the private and commercial needs of the rapidly growing county. A Klamath Tribal Agency - sponsored sawmill was completed in 1870 for the purpose of constructing the Agency. After signing the 1864 treaty, members of the Klamath Tribes were forcibly placed upon the Klamath Indian Reservation. At the time there was tension between the Klamath and the Modoc. A band of Modoc left the reservation to return to Northern California. They were defeated by the US Army after the Modoc War (1872–73), and were forced to return to Oregon.

By 1873, Tribal members were selling lumber to Fort Klamath and many other private parties, and by 1896 the sale to parties outside of the reservation was estimated at a quarter of a million board feet. With the arrival of the railroad in 1911, reservation timber became extremely valuable. The economy of Klamath County was sustained by it for decades. By the 1950s the Klamath Tribes were one of the wealthiest Tribes in the United States. They owned and judiciously managed for long term yield, the largest remaining stand of Ponderosa pine in the west. We were entirely self-sufficient. They were the only tribes in the United States that paid for all the federal, state and private services used by their members.

The Klamath tribe in Oregon was terminated under the Klamath Termination Act, or Public Law 587, enacted on August 13, 1954, as part of the US Indian termination policy. Under this act, all federal supervision over Klamath lands, as well as federal aid provided to the Klamath because of their special status as Indians, was terminated. The legislation required each tribal member to choose between remaining a member of the tribe, or withdrawing and receiving a monetary payment for the value of the individual share of tribal land. Those who stayed became members of a tribal management plan. This plan became a trust relationship between tribal members and the United States National Bank in Portland, Oregon. Of the 2,133 members of the Klamath tribe at the time of termination, 1,660 decided to withdraw from the tribe and accept individual payments for land.

After being terminated, the tribe was cut off from services for education, health care, housing and related resources. Termination directly caused decay within the tribe including poverty, alcoholism, high suicide rates, low educational achievement, disintegration of the family, poor housing, high dropout rates from school, disproportionate numbers in penal institutions, increased infant mortality, decreased life expectancy, and loss of identity.

The present-day Klamath Indian Reservation consists of twelve small non-contiguous parcels of land in Klamath County. These fragments are generally located in and near the communities of Chiloquin and Klamath Falls. Their total land area is 1.248 km² (308.43 acres). As is the case with many Native American tribes, today few of the Klamath tribal members live on the reservation; the 2000 census reported only nine persons resided on its territory, five of whom were white people. There is currently a dispute of blood quantum being discussed by tribal members.

There are currently around 4,500 enrolled members in the Klamath Tribes, with the population centered in Klamath County, Oregon. Most tribal land was liquidated when Congress ended federal recognition in 1954 under its forced Indian termination policy. Some lands were restored when recognition was restored. The tribal administration currently offers services throughout the county. (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Klamath_Tribes)

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.