TAKELMA INDIAN NATION

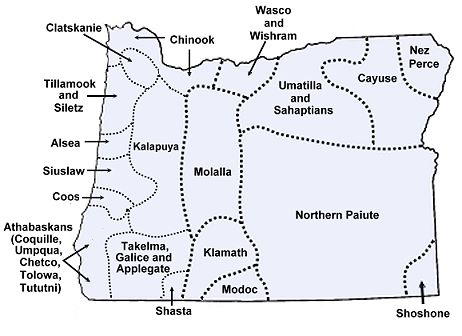

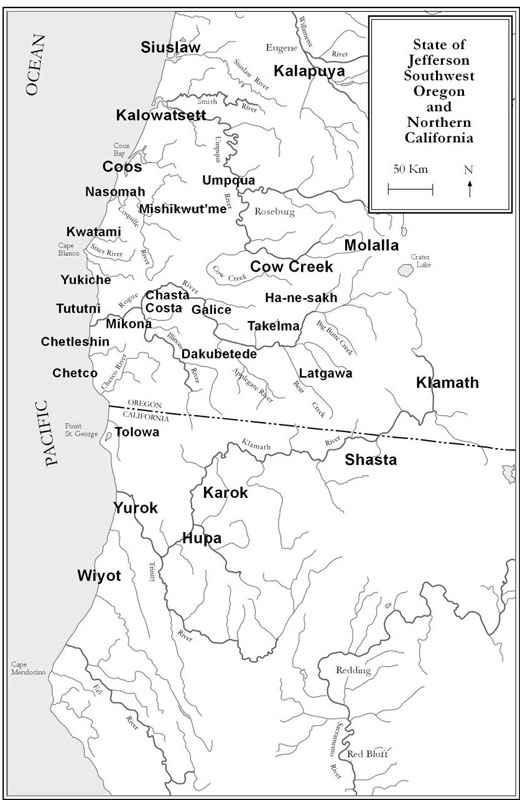

Location

Shelter

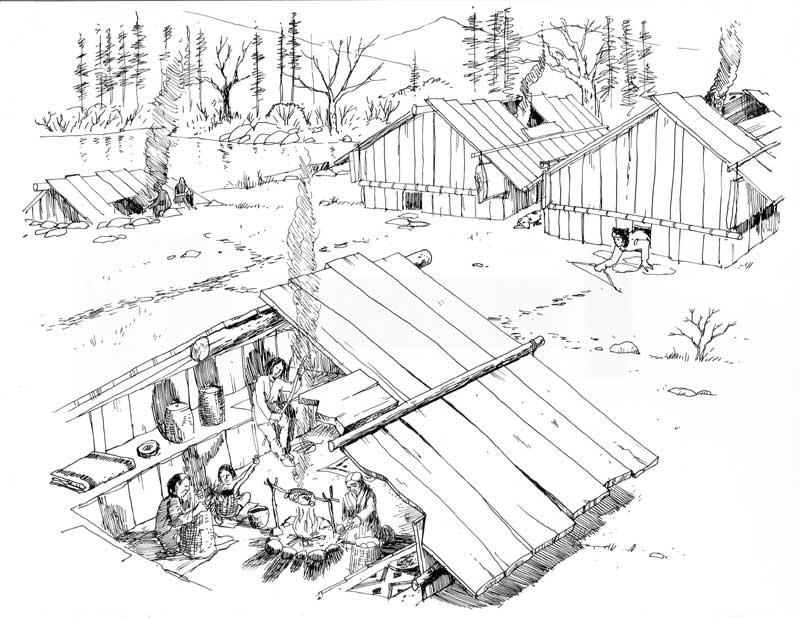

The house, quadrangular in shape and partly underground, was constructed of hewn timber and was provided with a central fireplace, a smoke-hole in the roof, and a raised door from which entrance was had by means of a notched ladder. The sweat house, holding about six, was also a plank structure, though smaller in size; it was reserved for the men.(http://www.accessgenealogy.com/native/takelma-tribe.htm)

Food

Their main dependence for food was the acorn, which, after shelling, pounding, sifting, and seething, was boiled into a mush. Other vegetable foods, such as the camas root, various seeds, and berries (especially manzanita), were also largely used. Tobacco was the only plant cultivated. Of animal foods the chief was salmon and other river fish caught by line, spear, and net; deer were hunted by running them into an inclosure provided with traps. For winter use roasted salmon and cakes of camas and deer fat were stored away. (http://www.accessgenealogy.com/native/takelma-tribe.htm)

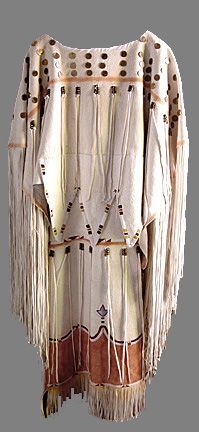

Clothing

In clothing and personal adornment the Takelma differed but little from the tribes of north California, red-headed-woodpecker scalps and the basket caps of the women being perhaps the most characteristic articles. Facial painting in red, black, and white was common, the last named color denoting war. Women tattooed the skin in three stripes; men tattooed the left arm with marks serving to measure various lengths of strings of dentalia. (http://www.accessgenealogy.com/native/takelma-tribe.htm)

Tools and Weapons

The main utensils were a great variety of baskets (used for grinding acorns, sifting, cooking, carrying burdens, storage, as food receptacles, and for many other purposes), constructed generally by twining on a hazel warp. Horn, bone, and wood served as material for various implements, as spoons, needles, and root diggers. Stone was hardly used except in the making of arrowheads and pestles. (http://www.accessgenealogy.com/native/takelma-tribe.htm)

Climate and Environment

**Much less is known about the lifeways of the Takelma Indians than about their neighbors in other parts of Oregon and northern California. Their homeland was settled by Euroamericans late in the history of the American Frontier, because the surrounding mountainous country protected it. But once colonization began, it proceeded rapidly. The discovery of gold spurred the first white settlement of the region in 1852. The Takelma who survived were sent to reservations in 1856. Settlers and natives lived in the region together for less than four years.Because Takelma territory included the most agriculturally attractive part of the Rogue Valley, particularly along the Rogue River itself, their valuable land was preferentially seized and settled by Euroamerican invaders in the mid-19th century. Almost without exception, these newcomers had little or no interest in learning about their indigenous neighbors, and they considered them a dangerous nuisance. They recorded little about the Takelma, beyond documenting their own perspective on conflicts. Native Americans living near the Takelma but on more marginal and rugged land, such as the Shastan and Rogue River Athabascan peoples, survived the colonization period with their cultures and languages more intact.

Conflicts between the settlers and the indigenous peoples of both coastal and interior southwest Oregon escalated and became known as the Rogue River Wars. Nathan Douthit examined peaceful encounters between the whites and southern Oregon Indians, encounters he describes as "middle-ground" interactions, undertaken by "cultural intermediaries." Douthit argues that without such "middle-ground" contact, the Takelma and other southern Oregon Indians would have been exterminated rather than relocated.

In 1856, the U.S. government forcibly relocated the Takelma who survived the Rogue Indian Wars to the Coast Indian Reservation (today the Siletz Reservation) on the rainy northern Oregon coast, an environment much different from the dry oak and chaparral country that they knew. Many died on the way to the Siletz Reservation and the Grand Ronde Indian Reservation, which now exists as Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde Community of Oregon. And many died on the reservations from disease, despair and inadequate diet. Indian agents taught the surviving Takelma farming skills and discouraged them from speaking their own language, believing that their best chance for productive lives depended on their learning useful skills and the English language. On the reservations, the Takelma lived with Native Americans from different cultures, and intermarriage with people of other cultures, both on and off the reservation, worked against the transmission of Takelman language and culture to Takelman descendants.

The Takelma spent many years in exile before anthropologists began to interview them and record information about their language and lifeways. Linguists Edward Sapir and John Peabody Harrington worked with Takelma descendants.

In the 2010 census, 16 people claimed Takelma ancestry, 5 of them full-blooded.

Environment and adaptationThe Takelman people lived as foragers, a term that many anthropologists consider more exact than hunter-gatherers. They collected plant foods and insects, fished and hunted. The Takelma cultivated only one crop, a native tobacco (Nicotiana biglovii) . The Takelma lived in small bands of related men and their families. Interior southwest Oregon has pronounced seasons and the ancient Takelma adapted to these seasons by spending spring, summer and early fall months collecting and storing food for the winter season. The Rogue River, around which their villages nucleated, provided them with salmon and other fish. Ancient salmon runs were reputedly large. The intensive and coordinated labor involved in large-scale capture of salmon with nets and spears by men and their cleaning and drying by women provided the Takelma with an excellent, protein-rich diet for much of the year, if the salmon runs were good. The salmon diet was supplemented—or replaced in years of poor salmon runs—by game such as deer, elk, beaver, bear, antelope and bighorn sheep. (The last two species are now locally extinct.) Smaller mammals, such as squirrels, rabbits and gophers, might be snared by either men or women. Yellowjacket larvae and grasshoppers also provided calories.

The limiting factor in the Takelma diet was carbohydrates, since fish and game provided abundant fat and protein. To get the carbohydrates and vitamins needed for good health, the Takelma collected a variety of plant foods. However, consistent with optimal foraging theory, which suggests that humans, like other creatures, decide what foods to eat depending on what gives the greatest nutritional value for the work expended to get it, the Takelma strategically focused on two plant foods: acorns and camas, also known as camassia. They harvested acorns from the two species of oaks in their Rogue Valley territory, Oregon white oak and California black oak. When these foods were not available, or for variety in their diet, Takelma women also gathered and processed the seeds of native grasses and tarweed (Madia elegans), dug roots and collected small fruits.

DwellingsDuring the winter months, the Takelma lived in semi-subterranean homes dug partly into the insulating earth with super-structures built of vertically placed Sugar pine planks. Poorer people also lived in pole-and-bark dwellings, well banked with earth and dry leaves for insulation. Typically the planks rested on two 6 feet tall vertical shafts that supported a horizontal central pole. Beds of cat-tail mats were placed adjacent to the fire pit, with opening in the roof to allow for ventilation. Takelma homes bore structural similarities to the semi-subterranean homes of the Klamath and Modoc peoples to the east, who spoke languages in the Plateau Penutian family, and to those of the Shasta to the south, who spoke various Shastan languages (which may be part of the hypothetical Hokan family). One historical account describes a rectangular, plank structure large enough to hold 100 people, but archaeologists in the region have typically found remains of much smaller dwellings. During the warmer months of Summer Takelma lived in residencies were made of brush or forgoed them altogether. (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Takelma)

**The Takelma of the upper Rogue River are perhaps the best documented Native group of the region due to anthropologist Edward Sapir’s work early in the twentieth century. The Takelma, as defined by language dialect, comprised two, and possibly three distinct groups. The principal villages of the Lowland Takelma centered along the Rogue River extending from the present-day town of Gold Hill downriver to about Grave Creek. The Upland Takelma winter village home territory lay further upriver in the lower Bear Creek Valley near Table Rock (near Medford), as far east as Ashland, and in the Little Butte Creek drainage.

The Takelma augmented their staple vegetal foods of acorns and camas with a variety of root crops, manzanita berries, pine nuts, tarweed seeds, wild plums, and sunflowers. They found protein in anadromous fish—especially salmon—deer, and elk, as well as in rabbits, squirrels, and certain insects. The Takelma fished for salmon during the seasonal spawning runs that occurred at various times throughout the year, although not every fish-bearing stream had runs of fish every season.

The Takelma located their permanent winter villages in the region’s low elevation river valleys near predictable major food resources such as reliable fishing locations and acorn groves. During the warmer months they moved to seasonal base camps in the surrounding uplands to hunt, to gather ripening crops, and to procure materials for chipped-stone tools.

The Takelma’s seasonally fluctuating staple food sources and their need to gather widely scattered vegetable and animal foods in the upland areas had the effect of isolating families and communities. These periods of isolation hindered development of any strong central authority in the region. Instead, the local village community formed the principal social and political unit.

In the Takelma worldview, supernatural spirits associated with plants and animals—believed to be manifestations of primeval earthly inhabitants—determined nature’s forces and human fate. A few Takelma myths concerning the activities of these supernatural beings have survived, relayed by older Native informants to early twentieth-century ethnographers. People taught their children through stories how to survive in nature. Tales of Coyote, Beaver, and Acorn Woman taught people how to protect deer herds from over-hunting and about drought, famine, and floods. In the story of Rainmaker, for example, “A stout man named Khu-khu-w came…to Table Rock and the Rogue River was low and the Table Rock Indians could not catch salmon. The Table Rock Indians hired that man to make rain, and it flooded all this lowland.” (http://www.ohs.org/education/oregonhistory/narratives/subtopic.cfm?subtopic_ID=232)

Conflicts between the settlers and the indigenous peoples of both coastal and interior southwest Oregon escalated and became known as the Rogue River Wars. Nathan Douthit examined peaceful encounters between the whites and southern Oregon Indians, encounters he describes as "middle-ground" interactions, undertaken by "cultural intermediaries." Douthit argues that without such "middle-ground" contact, the Takelma and other southern Oregon Indians would have been exterminated rather than relocated.

In 1856, the U.S. government forcibly relocated the Takelma who survived the Rogue Indian Wars to the Coast Indian Reservation (today the Siletz Reservation) on the rainy northern Oregon coast, an environment much different from the dry oak and chaparral country that they knew. Many died on the way to the Siletz Reservation and the Grand Ronde Indian Reservation, which now exists as Confederated Tribes of the Grand Ronde Community of Oregon. And many died on the reservations from disease, despair and inadequate diet. Indian agents taught the surviving Takelma farming skills and discouraged them from speaking their own language, believing that their best chance for productive lives depended on their learning useful skills and the English language. On the reservations, the Takelma lived with Native Americans from different cultures, and intermarriage with people of other cultures, both on and off the reservation, worked against the transmission of Takelman language and culture to Takelman descendants.

The Takelma spent many years in exile before anthropologists began to interview them and record information about their language and lifeways. Linguists Edward Sapir and John Peabody Harrington worked with Takelma descendants.

In the 2010 census, 16 people claimed Takelma ancestry, 5 of them full-blooded.

Environment and adaptationThe Takelman people lived as foragers, a term that many anthropologists consider more exact than hunter-gatherers. They collected plant foods and insects, fished and hunted. The Takelma cultivated only one crop, a native tobacco (Nicotiana biglovii) . The Takelma lived in small bands of related men and their families. Interior southwest Oregon has pronounced seasons and the ancient Takelma adapted to these seasons by spending spring, summer and early fall months collecting and storing food for the winter season. The Rogue River, around which their villages nucleated, provided them with salmon and other fish. Ancient salmon runs were reputedly large. The intensive and coordinated labor involved in large-scale capture of salmon with nets and spears by men and their cleaning and drying by women provided the Takelma with an excellent, protein-rich diet for much of the year, if the salmon runs were good. The salmon diet was supplemented—or replaced in years of poor salmon runs—by game such as deer, elk, beaver, bear, antelope and bighorn sheep. (The last two species are now locally extinct.) Smaller mammals, such as squirrels, rabbits and gophers, might be snared by either men or women. Yellowjacket larvae and grasshoppers also provided calories.

The limiting factor in the Takelma diet was carbohydrates, since fish and game provided abundant fat and protein. To get the carbohydrates and vitamins needed for good health, the Takelma collected a variety of plant foods. However, consistent with optimal foraging theory, which suggests that humans, like other creatures, decide what foods to eat depending on what gives the greatest nutritional value for the work expended to get it, the Takelma strategically focused on two plant foods: acorns and camas, also known as camassia. They harvested acorns from the two species of oaks in their Rogue Valley territory, Oregon white oak and California black oak. When these foods were not available, or for variety in their diet, Takelma women also gathered and processed the seeds of native grasses and tarweed (Madia elegans), dug roots and collected small fruits.

DwellingsDuring the winter months, the Takelma lived in semi-subterranean homes dug partly into the insulating earth with super-structures built of vertically placed Sugar pine planks. Poorer people also lived in pole-and-bark dwellings, well banked with earth and dry leaves for insulation. Typically the planks rested on two 6 feet tall vertical shafts that supported a horizontal central pole. Beds of cat-tail mats were placed adjacent to the fire pit, with opening in the roof to allow for ventilation. Takelma homes bore structural similarities to the semi-subterranean homes of the Klamath and Modoc peoples to the east, who spoke languages in the Plateau Penutian family, and to those of the Shasta to the south, who spoke various Shastan languages (which may be part of the hypothetical Hokan family). One historical account describes a rectangular, plank structure large enough to hold 100 people, but archaeologists in the region have typically found remains of much smaller dwellings. During the warmer months of Summer Takelma lived in residencies were made of brush or forgoed them altogether. (http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Takelma)

**The Takelma of the upper Rogue River are perhaps the best documented Native group of the region due to anthropologist Edward Sapir’s work early in the twentieth century. The Takelma, as defined by language dialect, comprised two, and possibly three distinct groups. The principal villages of the Lowland Takelma centered along the Rogue River extending from the present-day town of Gold Hill downriver to about Grave Creek. The Upland Takelma winter village home territory lay further upriver in the lower Bear Creek Valley near Table Rock (near Medford), as far east as Ashland, and in the Little Butte Creek drainage.

The Takelma augmented their staple vegetal foods of acorns and camas with a variety of root crops, manzanita berries, pine nuts, tarweed seeds, wild plums, and sunflowers. They found protein in anadromous fish—especially salmon—deer, and elk, as well as in rabbits, squirrels, and certain insects. The Takelma fished for salmon during the seasonal spawning runs that occurred at various times throughout the year, although not every fish-bearing stream had runs of fish every season.

The Takelma located their permanent winter villages in the region’s low elevation river valleys near predictable major food resources such as reliable fishing locations and acorn groves. During the warmer months they moved to seasonal base camps in the surrounding uplands to hunt, to gather ripening crops, and to procure materials for chipped-stone tools.

The Takelma’s seasonally fluctuating staple food sources and their need to gather widely scattered vegetable and animal foods in the upland areas had the effect of isolating families and communities. These periods of isolation hindered development of any strong central authority in the region. Instead, the local village community formed the principal social and political unit.

In the Takelma worldview, supernatural spirits associated with plants and animals—believed to be manifestations of primeval earthly inhabitants—determined nature’s forces and human fate. A few Takelma myths concerning the activities of these supernatural beings have survived, relayed by older Native informants to early twentieth-century ethnographers. People taught their children through stories how to survive in nature. Tales of Coyote, Beaver, and Acorn Woman taught people how to protect deer herds from over-hunting and about drought, famine, and floods. In the story of Rainmaker, for example, “A stout man named Khu-khu-w came…to Table Rock and the Rogue River was low and the Table Rock Indians could not catch salmon. The Table Rock Indians hired that man to make rain, and it flooded all this lowland.” (http://www.ohs.org/education/oregonhistory/narratives/subtopic.cfm?subtopic_ID=232)

Your browser does not support viewing this document. Click here to download the document.

| takelma_indians.pdf | |

| File Size: | 7744 kb |

| File Type: | |